A fresh approach to diabetes (2013)

Type 2 diabetes is often caused by obesity, and weight-loss surgery usually reverses it. However, we don’t know precisely how this happens, and a new study at the MWC aims to find out.

Obese people are at high risk of developing type 2 diabetes, which has downstream complications such as heart disease, stroke and kidney failure. So it was a revelation when bariatric surgery, originally a largely cosmetic procedure to achieve weight loss, was found to rapidly eliminate diabetes – often before any significant weight loss had occurred. And even more astonishingly, says MWC Deputy Director Peter Shepherd, the surgery dramatically reduces the risk that non-diabetics develop the condition.

Obese people are at high risk of developing type 2 diabetes, which has downstream complications such as heart disease, stroke and kidney failure. So it was a revelation when bariatric surgery, originally a largely cosmetic procedure to achieve weight loss, was found to rapidly eliminate diabetes – often before any significant weight loss had occurred. And even more astonishingly, says MWC Deputy Director Peter Shepherd, the surgery dramatically reduces the risk that non-diabetics develop the condition.

“That’s really compelling,” Peter says. It appears that bariatric surgery somehow alters the hormones that control appetite, satiety and aspects of glucose metabolism, some of which may be through changing gut bacteria.

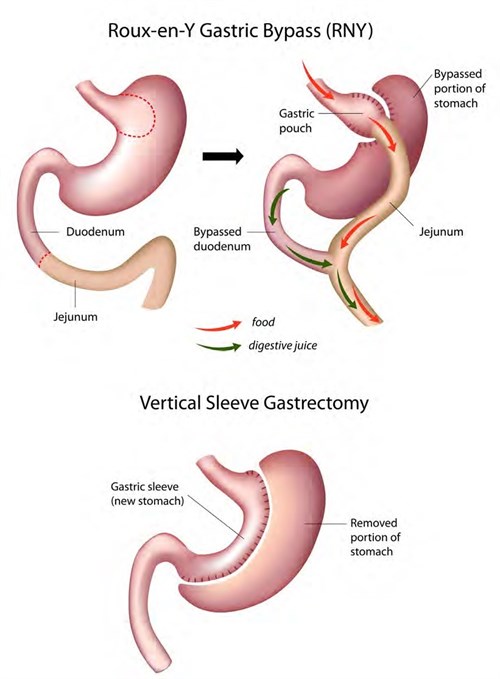

A MWC-funded study is underway to scrutinise the characteristics of gut hormones and bacteria in patients before and after two different types of bariatric surgery. The first is the Roux-En-Y gastric bypass, where the stomach is stapled down to the size of an egg then connected directly to the lower part of the small intestine, bypassing the rest of the stomach and the first part of the small intestine. The second is the sleeve gastrectomy, where the stomach pouch is made into a drastically smaller tube.

Leading the blinded randomised trial is MWC investigator Dr Rinki Murphy, an endocrinologist and senior lecturer in the Department of Medicine at the University of Auckland, working with Auckland bariatric surgeon Mr Michael Booth.

Pre-surgery, Rinki says, participants keep a food diary, complete an appetite assessment, and various measurements are made and samples taken to provide baseline data. These will be repeated at one and five years after the surgery; so far, 15 patients have just passed the one-year mark.

The hypothesis, she says, is that the Roux-En-Y, while technically more difficult surgery, leads to the most favourable hormonal changes in terms of diabetes and weight-loss “because the hormones released in relation to the same food consumed promote greater satiety”. Gut bacteria might be an untapped resource, too, she says – some microbiota may be more wasteful, or less efficient, at extracting energy from food after a Roux-En-Y compared to a sleeve gastrectomy.

The goal, she says, “is that we might be able to encourage the growth of wasteful bacteria and find novel treatments that promote the feeling of being full without having to go through surgery. Avoiding surgery is the ultimate aim, but we’re taking steps to find out what’s happening with these bacteria and hormones.”

Feature image: Schematic diagrams of two different types of bariatric surgery: the Roux-En-Y gastric bypass and (below) the sleeve gastrectomy.

© Alila07 | Dreamstime.com